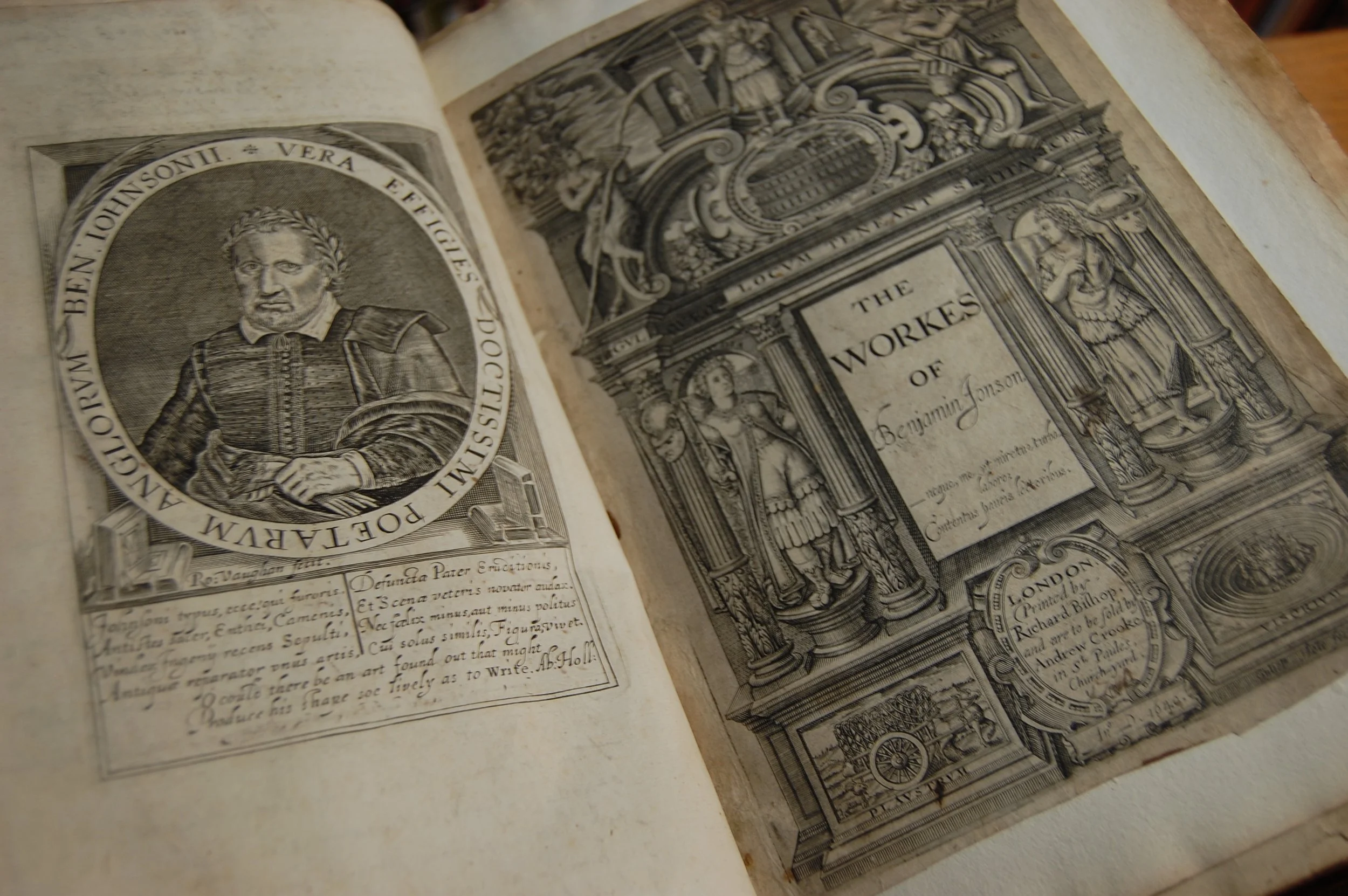

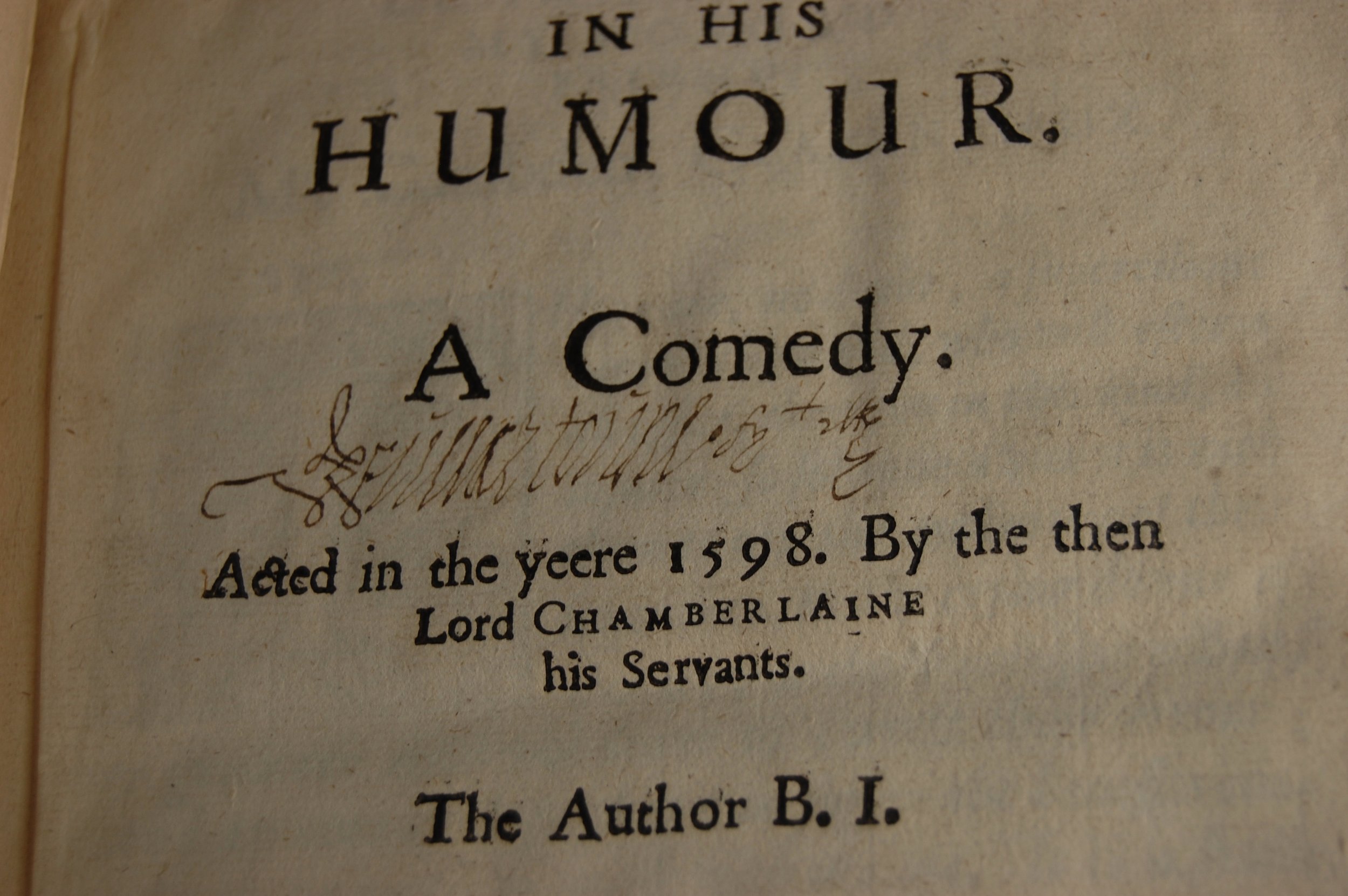

JONSON, Ben. The Workes of Benjamin Jonson. [Volume 1] London: Printed by Richard Bishop [and Robert Young], and are to be sold by Andrew Crooke in St Paules Churchyard. 1640.

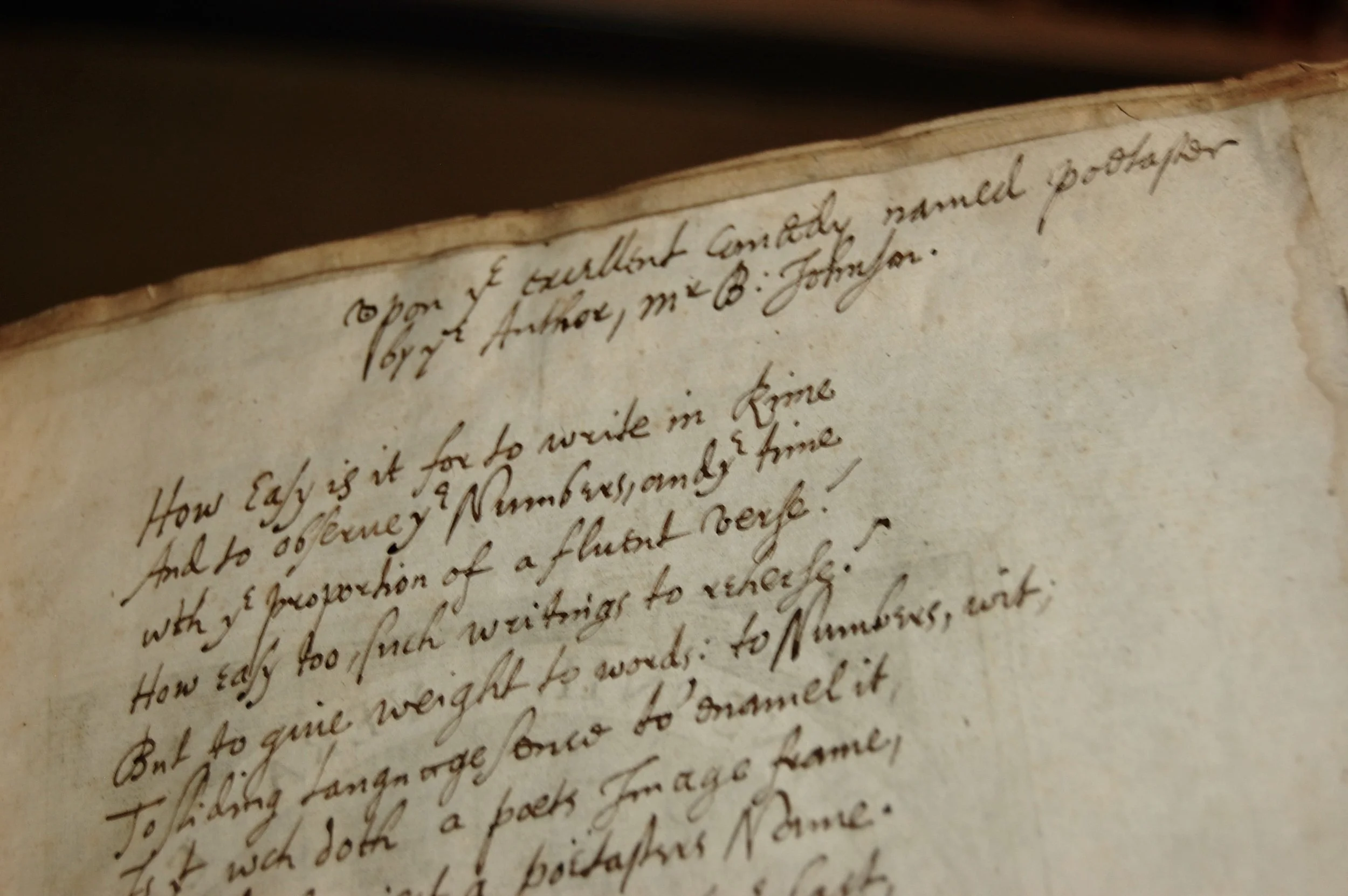

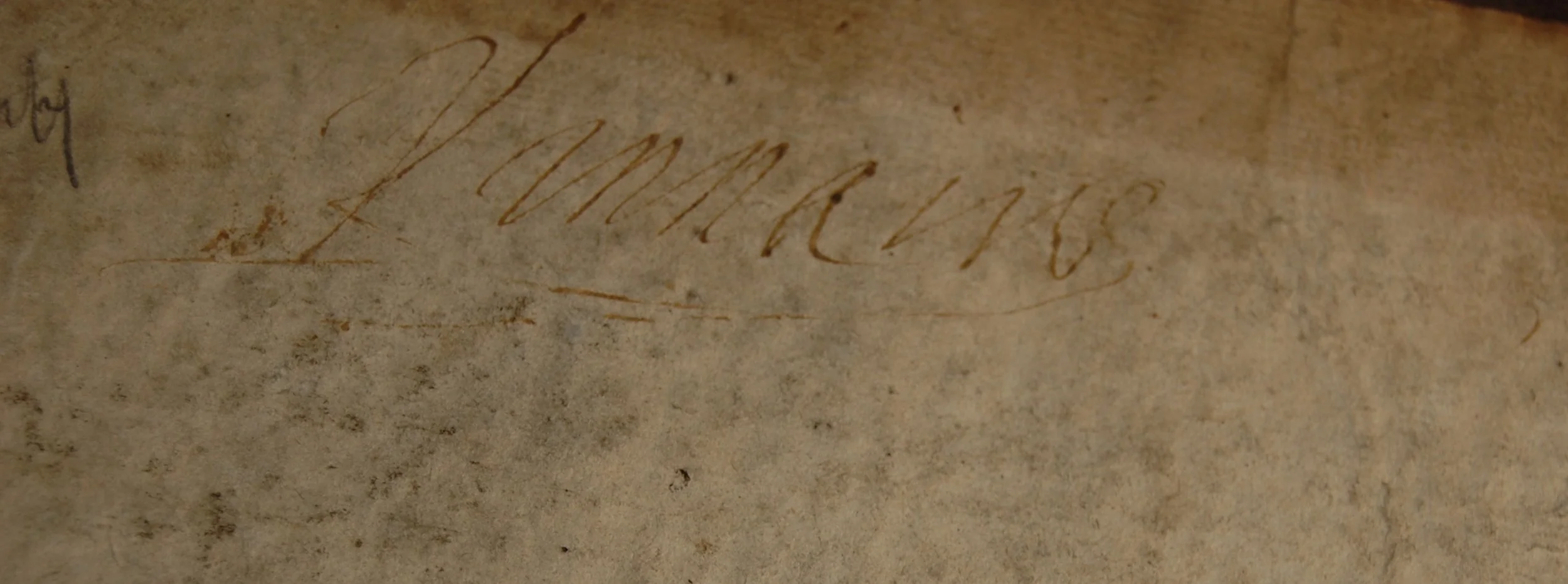

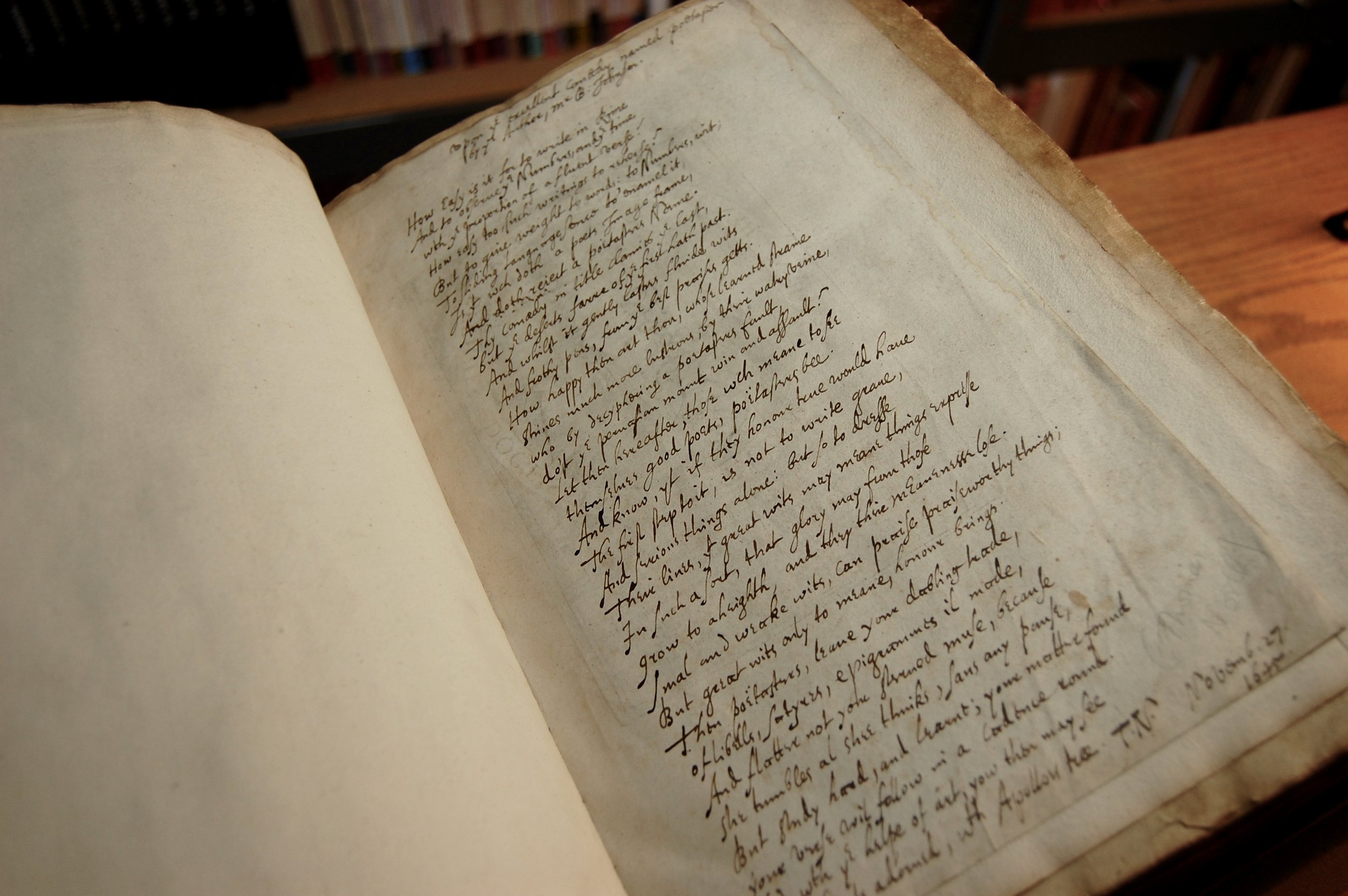

Contemporary brown calf boards, rebacked. Early manuscript criticism about Jonson’s Poetaster written on the recto of the portrait, apparently never published or analyzed before now. The exact transcript is given here; a modernized version is available at the bottom of the page.

upon ye excellent comœdy named poetaster

by ye Author, mr B: Johnson.

How easy is it for to write in Rime

And to observe ye Numbers, and ye time

wth ye proportion of a fluent verse!

How easy too, such writings to reherse!

But to give weight to words: to Numbers, wit;

To sliding Language sence to’enamel it,

Is yt wch doth a poets Image frame,

And doth reiect a poёtasters Name.

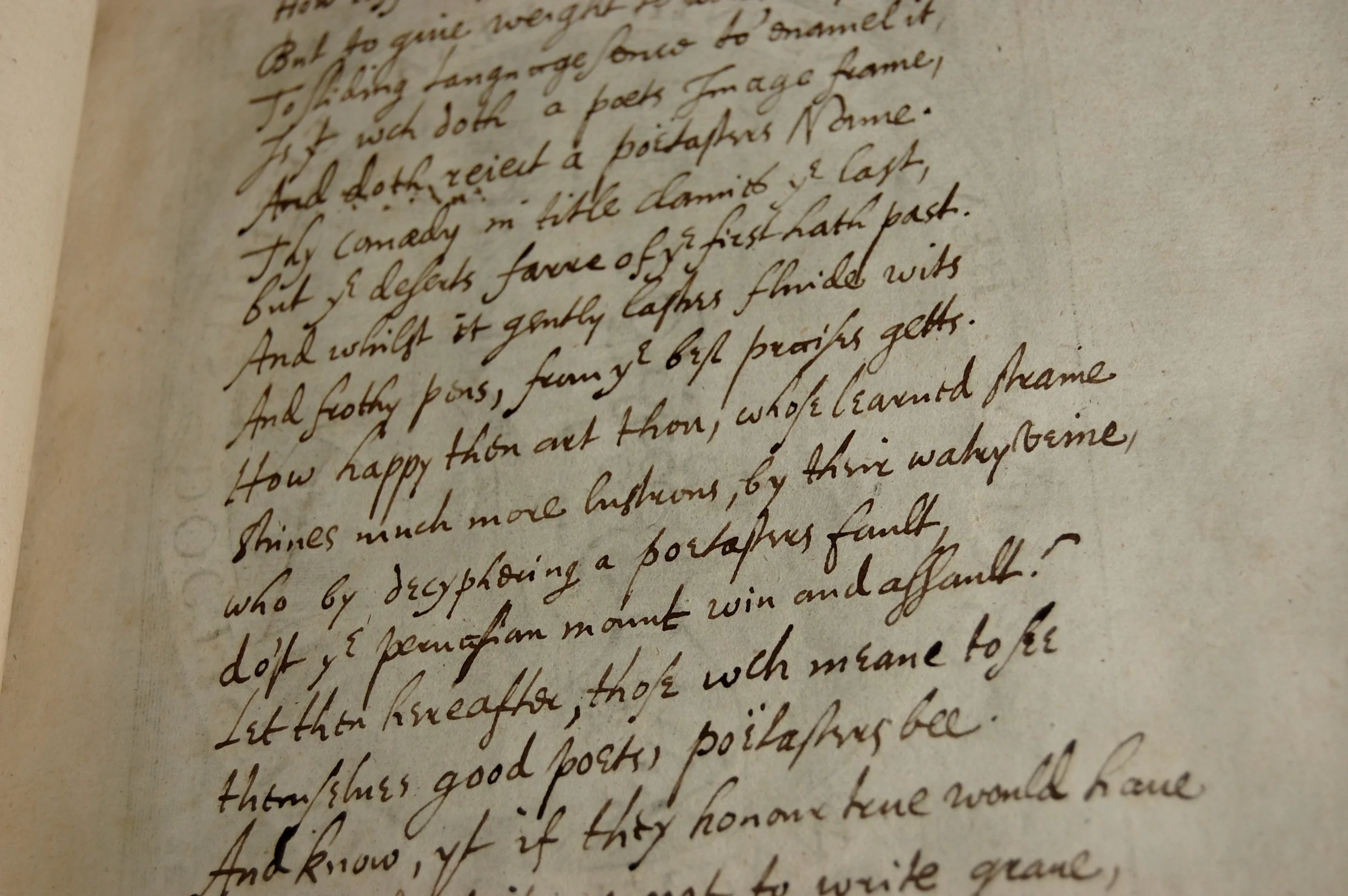

Thy comœdy in title dammes ye last,

But ye deserts farre of ye first hath past.

And whilst it gently lashes fluide wits

And frothy pens, from ye best praises getts.

How happy then art thou, whose learned streame

shines much more lustrous, by thire watry veine,

who by decyphering a poetasters fault,

do’st ye pernasian mount win and assault!

Let then hereafter, those wch meane to see

themselves good poets, poёtasters bee.

And know, yt if they honour true would haue

The first step to it, is not to write graue,

And serious things alone: but so to dresse

Their lines, yt great wits may meane things expresse

In such a sort, that glory may from those

grow to aheighth, and they thire meanenesse lose.

Smal and weake wits, can praise praiseworthy things;

But great wits only to meane, honour brings.

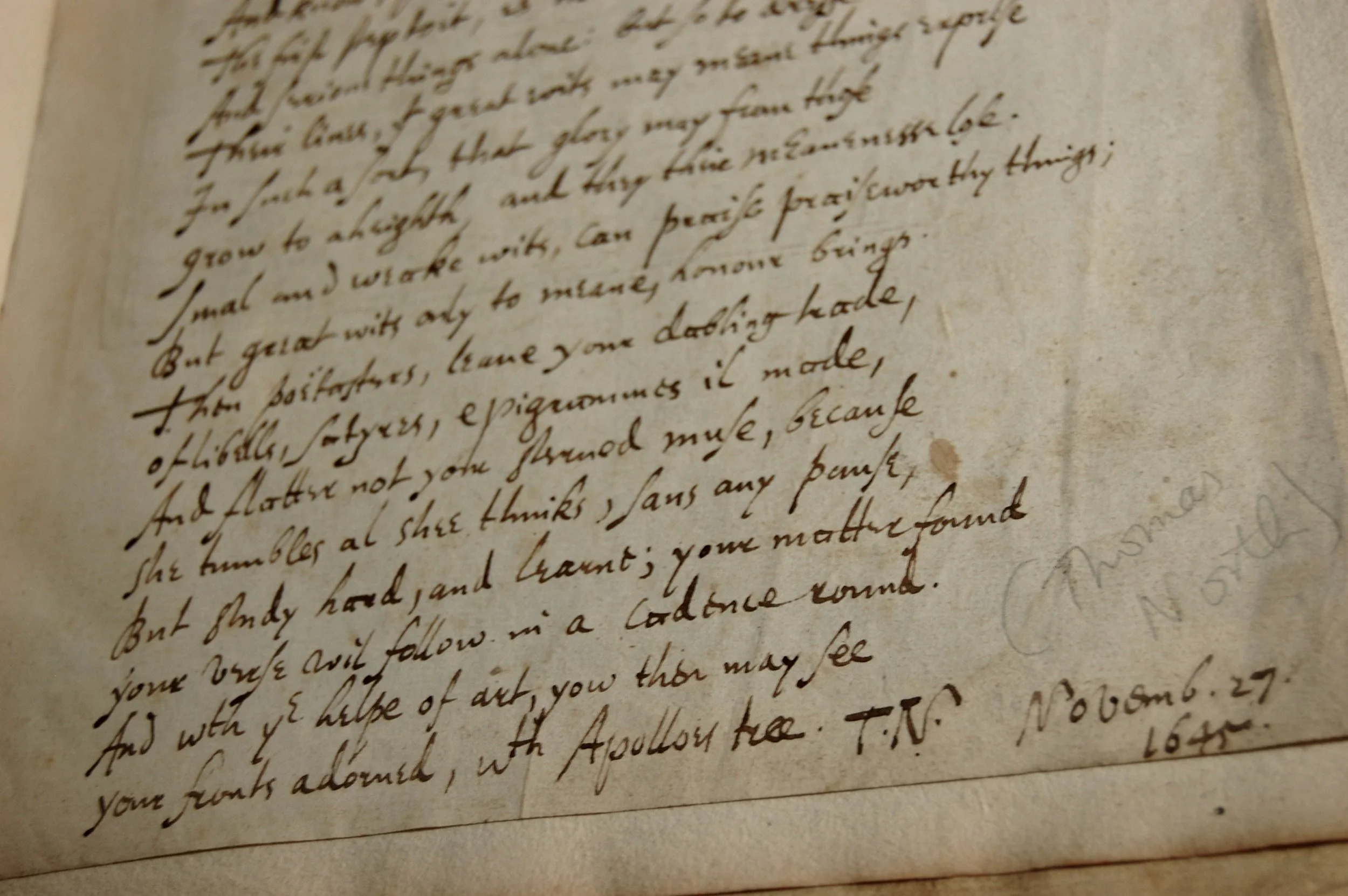

Then poёtasters, leaue your dabling trade

of libells, satyres, epigrammes il made,

And flattere not your sterued muse, because

she tumbles al shee thinks, sans any pause,

But study hard, and learne; youre matter found

your verse wil follow in a Cadence round.

And wth ye helpe of art, you then may see

your fonts adorned, wth Apolloes tree.

T.N. Novemb. 27.

1645

Poetaster was first performed in 1601 by the Children of the Chapel and published in quarto by Matthew Lownes in 1602. The play was one of Jonson’s contributions to the War of the Theatres, or Poetomachia (c. 1599-1601), a battle of wits and insults between Jonson, John Marston, and Thomas Dekker. This manuscript verse sympathizes with Jonson’s aims in Poetaster and praises his ability to create meaningful art out of humanity’s foibles, rather than relying solely on its virtues. Megan Heffernan and Brandi Adams suggest that the line about “libells, satyres, epigrammes il made” evokes the language of the 1599 Bishop’s Ban. Although the poem is written in present tense and would fit logically within the contemporary discourse surrounding the Poetomachia, this transcript is dated “Novemb. 27 1645.” Whether this is the date of composition and/or the date it was transcribed into the book is not clear. Nor is the identity of the scribe indicated – it could be “T.N.,” to whom the poem is ascribed, or an unknown book user who copied T.N.’s poem into this copy.

Moreover, who was T.N.? At some point, an unknown bookseller penciled in an attribution to Thomas North above “T.N.”; however, no source is given. Assuming that the bookseller was referring to Sir Thomas North, probably the best known and most literary Thomas North of the period, the suggestion is plausible. North died around 1603, giving him time, theoretically, to write this congratulatory verse to Jonson around the time of Poetaster’s first performance and publication. This would mean that the 1645 date refers to its moment of inscription in this copy; presumably, the scribe had access to the long-dead North’s poem, either in manuscript or some unknown published text.

However, many other possibilities exist. If the poem is a 1645 transcript of an earlier text, North was not the only T.N. in England. For example, in his “Life of Ben Jonson” in the Cambridge Jonson, Ian Donaldson suggests that one of Jonson’s acquaintances was likely Sir Thomas Neville (c. 1548-1615), master of Trinity College, Cambridge, who was apparently “a known supporter of theatrical performances in the university.”[1] As Amy Bowles notes, Neville also appears to have been involved in the circulation of plays in scribal manuscript, as evidenced by stationer Thomas Walkley’s dedication of Beaumont and Fletcher’s A King and No King (1619) to Neville: “I present, or rather returne unto your view, that [i.e. the playtext] which formerly hath beene received from you.”[2]

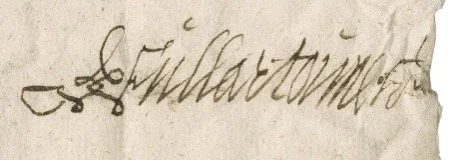

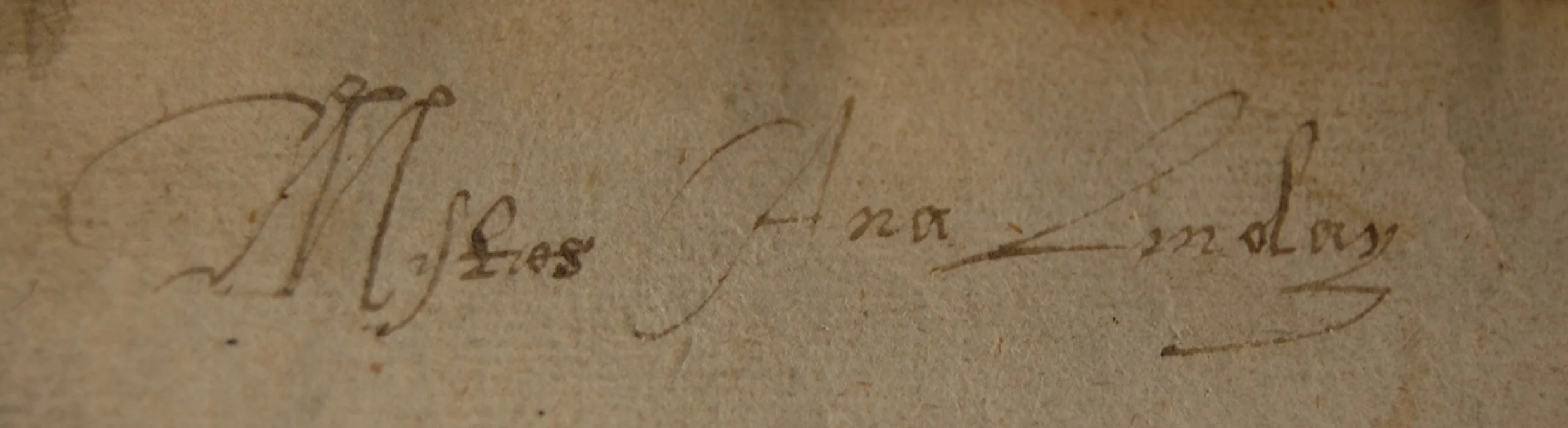

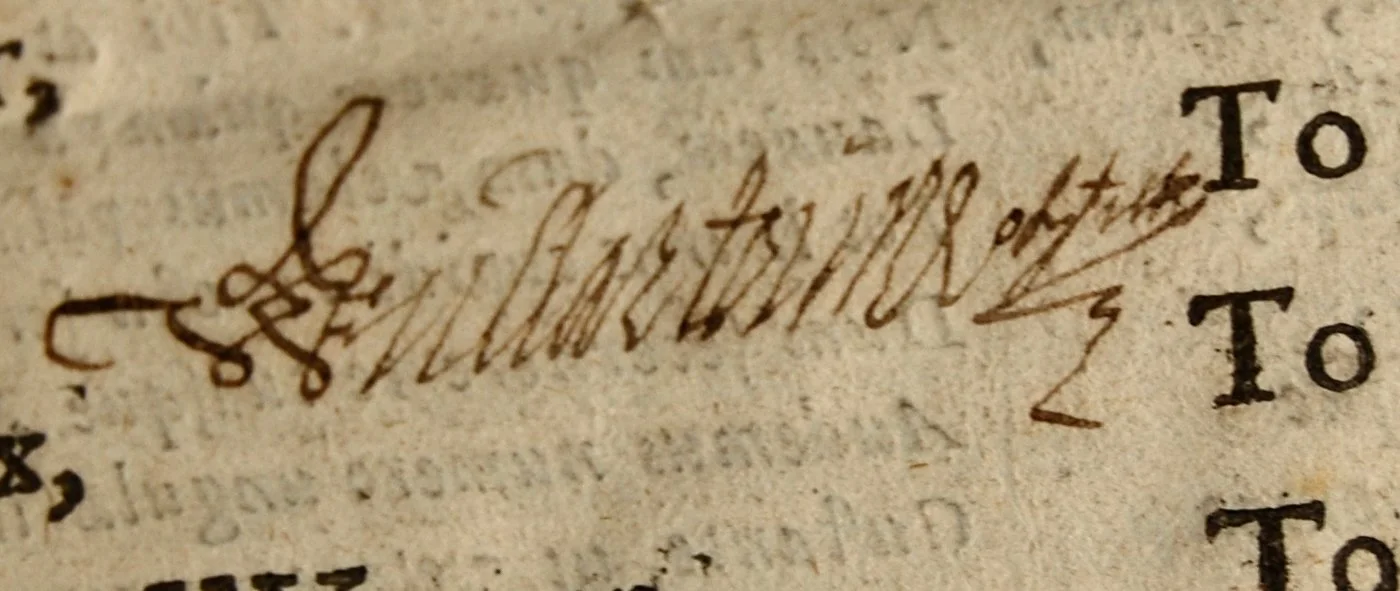

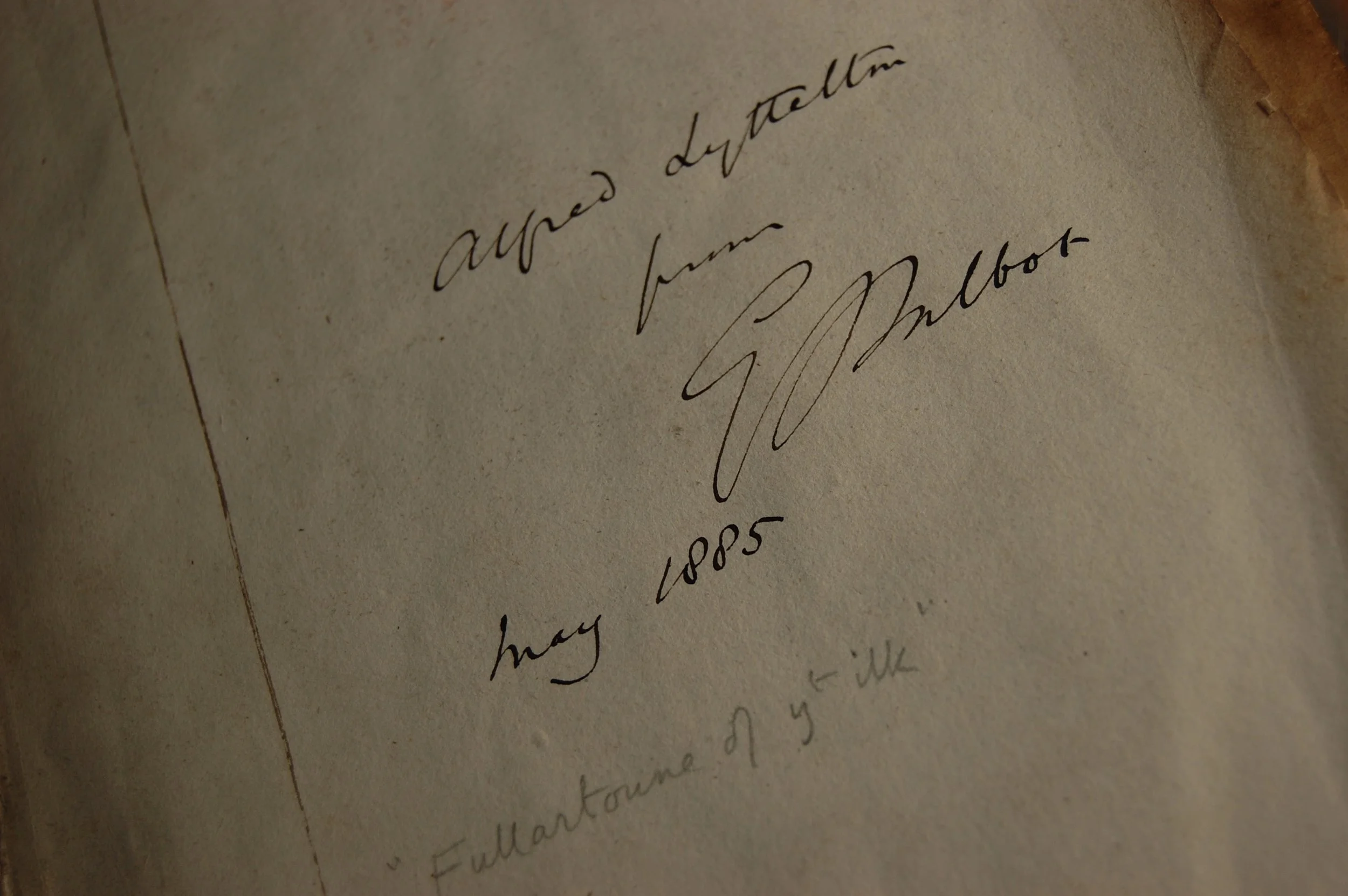

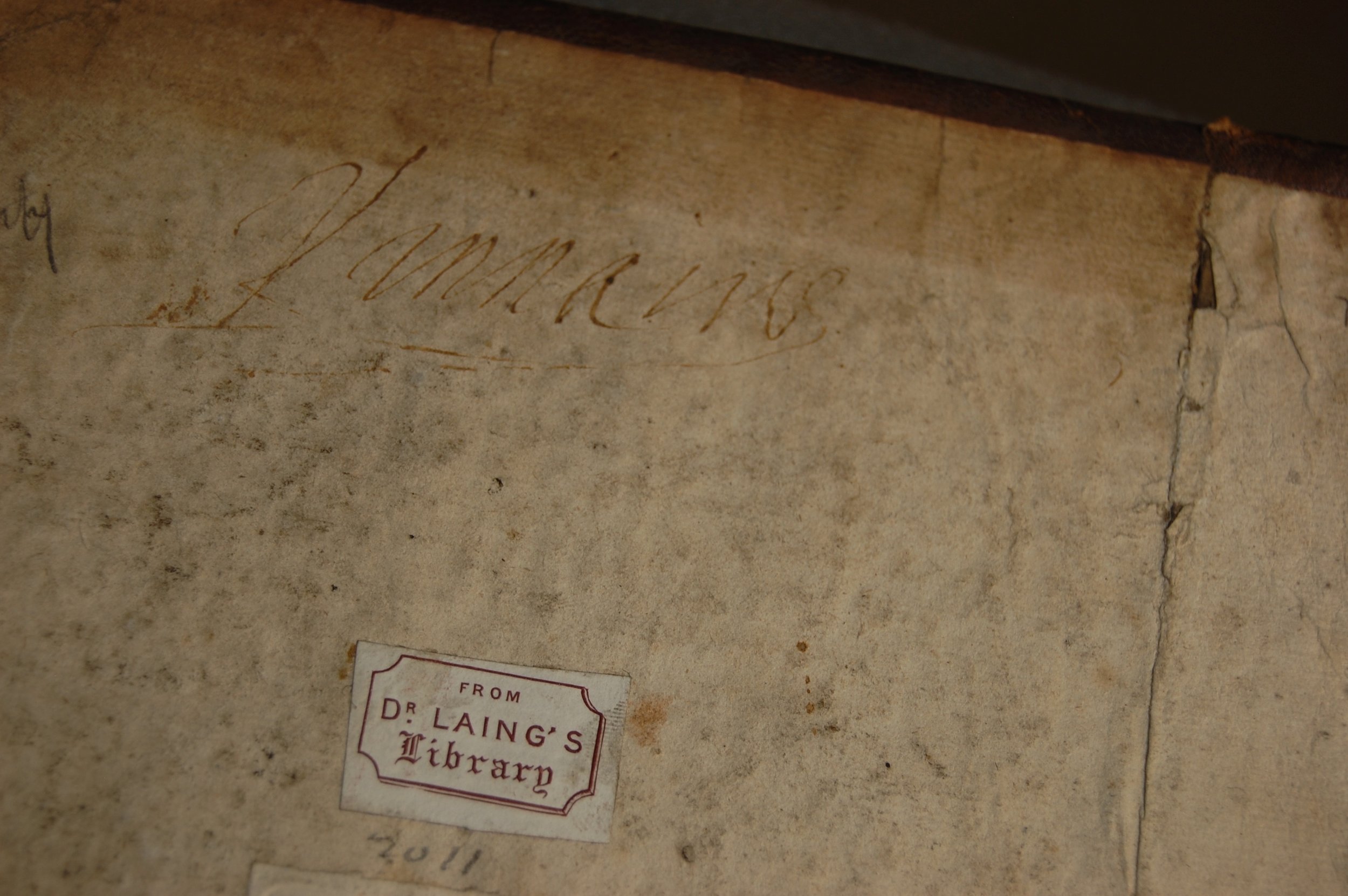

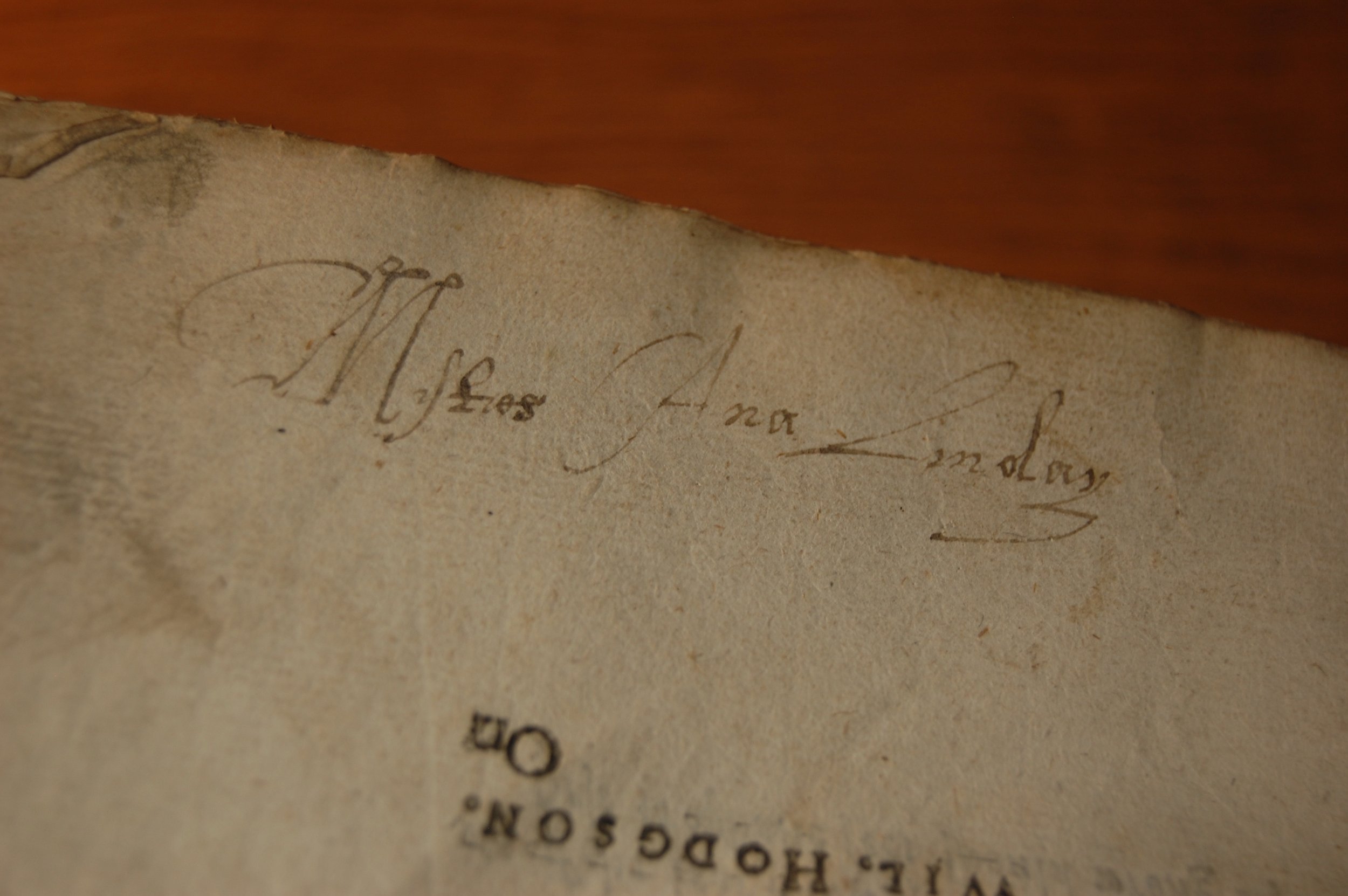

If 1645 is the date of the poem’s composition, we find ourselves untethered even farther from the possibilities among Jonson’s contemporaries. Whatever the date’s meaning, it situates the poem in some way to within five years of the book’s publication in 1640. What other evidence survives in the book itself that could hint at the author’s identity? The poem is the only dated marginalia in the book, but it is still possible to trace this copy’s provenance with some confidence. Two of the later bookplates, those of David Laing (1793-1878, “From Dr. Laing’s Library”) and John Drummond of Logy Almond, Esq (1712-1776) place the book in Scotland by the mid- to late-eighteenth century, where it stayed until the late nineteenth century. There are four other early inscriptions of note: “Kinnaird,” written above the bookplates on the front pastedown, “Fullarton of yt ilk,” written on the “Catalogue” (sig. A3r) and the title page of Every Man in his Humour (pg. 1), and “Mistres Ana Lind[s]ay,” (sig. A4r).

Provenance

The surnames Kinnaird, Lindsay, Fullarton/Fullerton, and Drummond locate this copy within a network of wealthy Scottish families in Perthshire. “Fullarton of yt ilk” is William Fullarton of Fullarton, confirmed by comparing his distinctive signature in this copy to letters digitized by the Folger from the Papers of the Rattray Family of Craighall (Folger X.c.61). The Folger collection contains letters from Fullarton dated between 1655 and 1665. This branch of the Fullarton family had settled near Meigle during the 15th/16th centuries. The William Fullarton in question appears to be the son of a William Fullarton who died c. 1628.

From Folger X.c.61 (69), Letter from William Fullerton to Patrick Rattray, dated 9 March 1663. Image digitized by the Folger Shakespeare Library. Creative Commons.

William the Younger married Margaret Lindsay (1623-? (at least 1697)), daughter of Alexander Lindsay, 2nd Lord Spynie, in 1648. Margaret’s younger sister was Anna/Anne Lindsay (1631-1707[?]). Anna never married, and contemporary legal documents refer to her as “Mistress Anna Lindsay.”[3] Although baptismal records confirm her birth in 1631, Anna’s death is harder to pin down. Various amateur family genealogists give her date of death as 1707; I can find no source for this information and must consider it suspect, but court documents dated 1699 suggest that she survived until at least the turn of the century.

Although William Fullarton’s vital dates are regrettably difficult to confirm, he may have been born in 1625 and died in 1680. If that is the case, his sister-in-law Anna Lindsay almost certainly outlived him, and may have taken possession of the book after his death, although multiple other scenarios are possible, including that Anna was the original owner of the book, and gave it to William. William’s wife and Anna’s sister, Margaret Lindsay Fullarton, was likely also involved in the book’s use/ownership at some point, although she did not inscribe it.

From the RHC copy of Jonson’s Workes.

Although this covers two of the early inscriptions, this leaves the poem, dated 1645, still unattributed. As discussed, “T.N.” may or may not have copied it into the book him/herself. Based on the letters in the Folger archives, William Fullarton’s handwriting is not a particularly good match for the poem-scribe’s, although the two seem to have shared a fondness for using “yt.” I have not found a sample of Anna Lindsay’s hand, so am unable to compare. Thus, the possibility remains that someone owned the Workes, and wrote down the poem (possibly in 1645), before Fullarton and Anna Lindsay used the book, or that their ownership was very brief, and that the book had passed into other hands between its publication in 1640 and the inscription in 1645 (if that is, indeed, the date that it was written in, not just a date of composition copied from elsewhere).

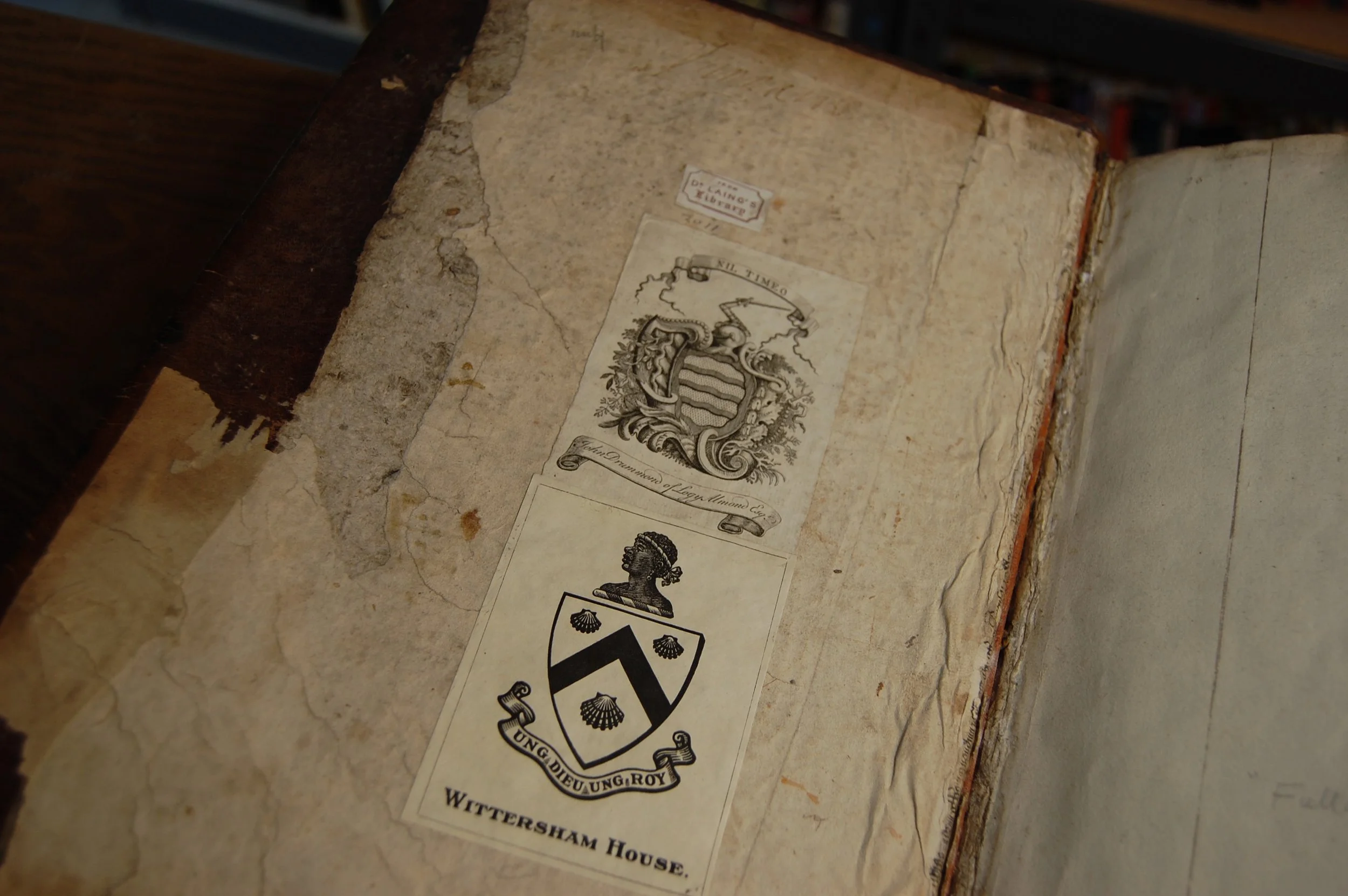

That leads us to the next four ownership marks, all on the front pastedown: the inscription “Kinnaird,” a small bookplate reading “From Dr Laing’s Library,” and two larger bookplates, the first of “John Drummond of Logy Almond” and the second of “Wittersham House.” [Note to the reader: please be aware that the Wittersham House bookplate, pictured below, includes an illustration of a racist stereotype of a black person.] For reasons I will explain later, I believe that the “Kinnaird” inscription predates the Drummond bookplate, which was placed by 1776 at the latest. The possible dates of William Fullarton’s ownership of the book range from 1640 till 1680 (uncertain). Anna Lindsay’s cover 1640 till 1707 (uncertain).

John Drummond of Logy Almond/Logiealmond (1712-1776), hereafter “John III,” was the great-grandson of John Drummond, 2nd Earl of Perth. The Drummonds were a large, well-connected family. John I, the 2nd Earl of Perth, had three sons: James, 3rd Earl of Perth, William, 2nd Earl of Ker, and Sir John Drummond. Sir John, or John II, purchased Logiealmond in 1668, and his grandson, John III, inherited it from his uncle, Thomas Drummond, in 1757. This therefore narrows the bookplate’s dates down to 1757-1776.

“Kinnaird” could be a surname, a place name (Kinnaird Castle, et. al.), a title (Lord Kinnaird), or an honorific (“of Kinnaird”). The likely association in this case is with the Kinnaird family of Inchture, first awarded the title of Lord Kinnaird in 1682. This possibility stands out because Anne Kinnaird, daughter of Patrick, 2nd Lord Kinnaird, married Thomas Drummond of Logiealmond, uncle of John III, of bookplate fame, in 1701. Ann Kinnaird’s first cousin John Hay, 12th Earl of Erroll, had already married Thomas Drummond’s first cousin Anne Drummond, daughter of the 3rd Earl of Perth, in 1674. Clearly, the connections between the Drummonds and the Kinnairds were reasonably strong around the turn of the 18th century.

The connection between the Fullarton/Lindsay owners and the Kinnairds could come via the Carnegies of Kinnaird. Margaret Carnegie, a Carnegie of Boysack and great-granddaughter of the 1st Earl of Northesk, married William Fullarton, grandson of William Fullarton and Margaret Lindsay, in 1702. Various Carnegies, Lindsays, and Kinnairds had been intermarrying for at least two hundred years, with a few Drummonds thrown in for good measure. The families’ seats in Meigle (Fullarton), Logiealmond (Drummond), Boysack (Lindsay/Carnegie), Inchture (Kinnaird), Inverkeilor (Carnegie), etc., all lay within approximately a thirty-mile radius of Dundee.[4]

Although the exact sequence of this book’s chain of custody may be impossible to determine with absolute certainty, the combined Fullarton/Lindsay/Kinnaird/Drummond provenance place this book definitively within their familial network in that geographical region before its acquisition and removal to Edinburgh, likely in the mid-19th century, by David Laing.

I suspect that David Laing (1793-1878) acquired this book because of his interest in the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden (1585-1649). Although William Drummond came from a different branch of the enormous Drummond family, he was known to be friends with his distant cousin John Drummond, the 2nd Earl of Perth and the great-grandfather of John III of Logiealmond. In 1782, Drummond of Hawthornden’s descendant donated the poet’s papers to the Scottish Society of Antiquaries, where they were later arranged and researched by Laing, who had already edited a list of the books Drummond had donated to Edinburgh University. Laing published on several aspects of the Drummond manuscripts and the family in the 1830s, including an edition of The Genealogy of the Most Noble and Ancient House of Drummond (1831) written in 1681 by William Drummond, 1st Viscount Strathallan.[5]

And of course, Laing’s interest in the Drummond family was specifically tied to Ben Jonson, particularly after Laing found, in antiquary Robert Sibbald’s papers, a transcript of Drummond of Hawthornden’s notes about the 1618 visit of his friend Jonson, previously known only in an abridged form. Laing subsequently edited Notes of Ben Jonson’s Conversations with William Drummond of Hawthornden (Shakespeare Society of London, 1842).[6] Laing, a second-generation bookseller, was (like his research subject William Drummond) a bibliophile who amassed an enormous personal library during his life in the trade. I suspect that Laing acquired this copy of Jonson’s Workes because of its connection to the Drummond family, perhaps even from the family directly. Sir William Drummond Steuart sold Logiealmond to William, 4th Earl of Mansfield, in 1846 – some of the library could have been dispersed then.

When Laing died in 1878, his library was split into bequests and items to be sold, with the sale taking place over many sessions through Sotheby’s. On December 4, 1879, the fourth day of the first part of the sale, lot 1875, a copy of the 1640 Workes, with portrait and engraved title, in calf, was sold.[7] The likely purchaser, “E. Talbot,” gave the book to Alfred Lyttelton, cricketer and politician, in May 1885, after which the book plate of Wittersham House, Lytellton’s residence, was added below Drummond’s book plate.

The combination of a copy of Jonson, owned by the family of Jonson’s friend and correspondent, containing what appears to be an early critical response to Jonson’s work, is obviously both tenuous and tantalizing. The possibility that Drummond of Hawthornden himself, who lived until 1649, owned the copy, or that a member of his family found this poem among Drummond’s papers and transcribed it into this copy, feels farfetched but not impossible. I suspect there’s every likelihood that it’s what Laing hoped was the case when he acquired the book; the fact that he never published anything about it suggests, to me, that he found no evidence to support this idea. Even without a solid Hawthornden connection, however, the poem and its presence in this copy of Jonson’s Workes remain a fascinating mystery, deserving serious consideration.

Dr. Molly G. Yarn

My thanks to Tara Lyons, Brandi Adams, Dianne Mitchell, Hester Lees-Jeffries, and Megan Heffernan for their input and assistance.

[1] Ian Donaldson, “Life of Ben Jonson | The Cambridge Works of Ben Jonson” <https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/essays/jonsons_life_essay/> [accessed 1 May 2022].

[2] Amy Bowles, “Dressing the Text: Ralph Crane’s Scribal Publication of Drama,” The Review of English Studies, 67.280 (2016), 405–27 (p. 407 n.9).

[3] The Sessional Papers, Printed by Order of the House of Lords, or Presented by Royal Command, in the Session 1847-8, Vol. XXII: Evidence Before Lords Committees for Privileges and Before the House, 1848, p. 528. There was another Anna Lindsay, a cousin, active around the same dates, who could conceivably have been the inscriber of this book, but since that Anna Lindsay, being the daughter of the Earl of Crawford, was known as “Lady Anna,” and less closely connected to Fullarton, I incline towards the first Anna. The extensive library of a different branch of the Lindsay family, the Lindsays of Edzell/Earls of Balcarres, has recently been documented in Kelsey Jackson Williams, Jane Stevenson, and William Zachs, A History and Catalogue of the Lindsay Library, 1570-1792: The Story of ‘Some Bonie Litle Bookes’ (Brill, 2022) <https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004503793>.

[4] One important exception to this is the poet William Drummond of Hawthornden, whose home, Hawthornden Castle, lies just south of Edinburgh,

[5] Strathallan was the grandson of James Drummond (1551-1623), 1st Lord Maderty, whose brother Patrick was John Drummond III’s great-great-grandfather.

[6] Ian Donaldson, “Informations to William Drummond of Hawthornden: Textual Essay” <https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/essays/Informations_textual_essay/> [accessed 19 April 2022].

[7] David Laing, Catalogue ... of the ... Library of the Late David Laing Esq., LL.D. ... Comprising an Extraordinary Collection of Works by Scottish Writers or Relating to Scotland ... Including Complete Series of the Publications of the Abbotsford, Bannatyne, and Other Literary Clubs; Transactions of Scotch & English Societies; Writings of Eminent Divines Historians and Topographers; First Editions ... &c. Which Will Be Sold by Auction, by Messrs. Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge ... (London: Dryden press, J. Davy and sons, 1879), p. 118 <https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/102836042> [accessed 14 April 2022]. This copy is distinguished by its binding material from another copy, in old morocco, sold on the sixth day.

MODERNIZED:

upon the excellent comedy named Poetaster

by the Author, Mr B. Jonson.

How easy is it for to write in Rhyme

And to observe the Numbers, and the time

with the proportion of a fluent verse!

How easy too, such writings to rehearse!

But to give weight to words: to Numbers, wit;

To sliding Language sense to’enamel it,

Is that which doth a poet’s Image frame,

And doth reject a poёtaster’s Name.

Thy comedy in title damns ye last,

But the desserts fair of the first hath past.

And whilst it gently lashes fluid wits

And frothy pens, from the best praises gets.

How happy then art thou, whose learned stream

shines much more lustrous, by their wat’ry vein,

who by deciphering a poёtaster’s fault,

dost the Parnassian mount win and assault!

Let then hereafter, those which mean to see

themselves good poets, poёtasters be.

And know, that if they honour true would have

The first step to it, is not to write grave,

And serious things alone: but so to dress

Their lines, that great wits may mean things express

In such a sort, that glory may from those

grow to a heighth, and they their meanness lose.

Small and weak wits, can praise praiseworthy things;

But great wits only to mean, honour brings.

Then poёtasters, leave your dabbling trade

of libels, satyres, epigrammes ill made,

And flatter not your sterved muse, because

she tumbles all she thinks, sans any pause,

But study hard, and learn; your matter found,

your verse will follow in a Cadence round.

And with the help of art, you then may see

your fonts adorned, with Apollo’s tree.

T.N. Novemb. 27.

1645